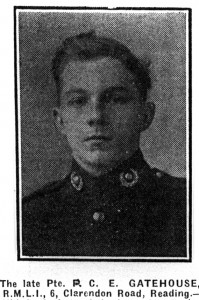

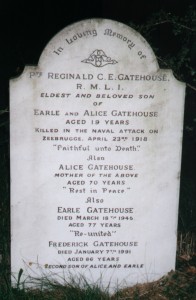

Reginald Charles Earle Gatehouse

Private CH/19258

“Zeebrugge” Battalion

Royal Marine Light Infantry

|

|

Reginald Gatehouse was born the 27 August 1897 the eldest son of Earle and Alice Gatehouse of, 6. Clarendon Road, Reading. In 1911 the family were living at 42. Clarendon Road. Earle Gatehouse’s occupation was given as a stableman jobmaster. Reginald then aged 12 and noted as being at school; he had two younger brothers and a baby sister. His maternal grandmother was also living with the family.

The Reading Standard of the 5 May 1918 outlined his service career. Reginald enlisted in the Royal Marine Light Infantry in October 1914, at the age of 16 years. After a period of training at Deal and Chatham he was placed on a monitor, the H.M.S. Roberts:

‘He spent 12 months in the Dardanelles, where he had many thrilling experiences and several miraculous escapes. On one occasion twelve of his comrades, who were on his ship at the time, were blown up by a shell, he being the only one uninjured. Later he was sent to Russia for special service and subsequently took part in the shelling of the Belgian coast by monitors’.

We are also told that he had been to France with his officer, who was engaged in a series of experiments and that Reginald had assisted him. We can only speculate on the nature of these experiments.

Five weeks before he was killed Reginald had been home on leave. On his return, preparations were in hand for the forthcoming strike at the German U-boat bases of Zeebrugge and Ostend. Described as a ‘Brilliant Naval Raid’ in the Chronology of War, Peter Liddle is much more circumspect in ‘The Sailor’s War 1914-1918’. German U-boats presented a considerable threat to shipping in the English Channel and in 1918 Vice Admiral Sir Roger Keyes was determined to strike a blow at the German U-boat bases. Unfortunately the raid on Zeebruge did not go quite according to plan.

During the attack Reginald Gatehouse was believed to have been on board HMS Iris, which, with HMS Daffodil, was one of two Mersey ferries being used in the attack. The HMS Iris came to the aid of the Vindictive and ensured the cruiser reached its objective by ramming it into the Mole at Zeebrugge. However, in the process HMS Iris drew heavy fire and of the platoon of forty-five men on board only twelve men were able to land.

An official Admiralty report described the raid:

“ with the exception of covering ships the force employed consisted of auxiliary vessels and six obsolete cruisers. Five of these filled with concrete, were used as blockships…and, in accordance with orders, were blown up and abandoned by their crews. Two blockships were sunk in the entrance to the Bruges Canal at Zeebrugge and a third ship grounded on the way in: storming parties landed on the Mole, which was much damaged by the blowing up of a submarine loaded with explosives. A German destroyer was torpedoed and other craft damaged. One British destroyer and two motorboats were lost. At Ostend two blockships were blown up. Storming parties were landed from ‘Vindictive’.”

Everyone concerned wanted to believe that there had been a great victory but in the event the attack was less decisive than was reported to the public. The blockships had sunk but not quite in the correct position and the gallantry of those who lost their lives or were wounded had achieved little. It was not too long before the U-boats were back in operation harassing the channel. However, the depressing events of the German spring offensive on the Western Front meant morale at home and at the front was low, so it was important to put a positive gloss on the Zeebrugge attack and much was made of the ability of the navy to strike decisively at the enemy.

The total casualties for the attack amounted to 16 officers, 86 men killed; 5 officers and 121 men wounded. Young Reginald Gatehouse was amongst the dead. He was 19 years old when killed in action 23 April 1918.

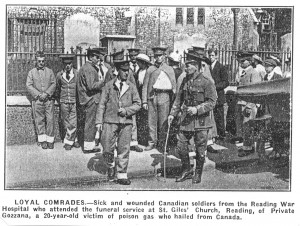

Reginald was brought home for burial, which took place at St. Peter’s Church, Earley. The funeral was a significant occasion and well attended by those who knew him. A picture of the scene at his funeral was published in the local paper.

|