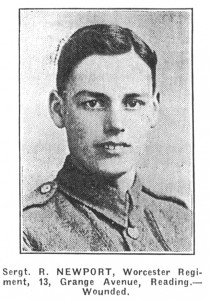

Reginald Newport

Signaller 20221

3rd (later 7th) Battalion Worcester Regiment

|

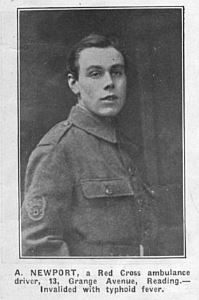

Reginald Newport was the son of Tom and Caroline Newport, of 13 Grange Avenue. The 1911 census indicates that he had two older brothers Albert and Ernest and an uncle Henry living in the family home. Father Tom was recorded as a wood saw sharpener at a timber merchants, Henry was a carpenter, brother Albert an apprentice to a motor engineer and Ernest a plumbers assistant. Reginald then 13 was still at school. Pictures of the brothers has been obtained from Berkshire and the War but it has not been possible to find any further details about their military service.

|

|

Reginald was last seen on 26th April 1918 and was reported missing. Parents were often desperate to find out where and how their sons had died and frequently had requests for information published in the papers. Reginald Newport’s mother was still seeking information about his end in a brief article published in the Standard October 18th 1919, his picture was published on page 7 of the same paper:

“203221 Sig. R. Newport – 7th Worcestershire Regt. Reported missing on April 26th 1918, now assumed to be dead. If any returned soldier knows anything concerning his end, would they kindly communicate with Mrs. Newport 13 Grange Avenue.”

In March 1918 the Germans began what was known as the “Spring Offensive”. Beginning with a long bombardment and using specially trained storm troopers the attack began with increasingly ferocious trench raids followed by Operation Michael which was aimed at the junction between the French and British Armies on the Somme. This was followed by Operation Georgette, along the River Lys. By 11th April Armentieres was evacuated and Haig issued this famous speech to his men “…..Every position must be held to the last man: there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall….each one of us must fight to the end.” On the 15th April the bloodily won ridge of Passchendaele was evacuated and the British divisions withdrew to a line around Ypres which approximated to that of 1915. The British were below full complement and the new men, replacing those lost in Third Ypres, were young and incompletely trained, although they fought bravely. On the 20th April there was a massive gas bombardment of the British line followed up by a further bombardment on the French on the 25th April. The Germans moved seven divisions forward and the British fell back to Dickebusch Lake. Whilst the French took the major force of the attack the British eventually were able to hold their positions. On the 29th April the Germans renewed their attack but it failed. The Second Battle of Lys was over. Losses were heavy 76,300 British and 35,000 French. (German casualties amounted to 109,300). Among the British losses was Reginald Newport.

Reginald Newport has no known grave and his name is commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing panels 75/77. Reginald Newport died aged 20 years.