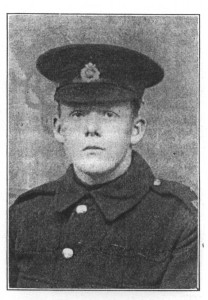

Fred Bird

Lance Corporal 102

24th Battalion Australian Imperial Force.

|

|

Fred Bird has no known grave, his name is commemorated on the Australian National War Memorial at Villers Bretonneux. The small town had been well behind British lines until April 1918 and the German Spring Offensive. The town was taken by the Germans on April 24th 1918 but recaptured the same evening by the Australians. Twelve hundred Australians lost their lives in the battle. The war memorial bears the names of all the Australians missing on the Somme battlefields.

From the top of the memorial tower the Cathedral spire at Amiens, away to the west, can be seen on a clear day and during spring and autumn months the trenches of the battlefield are outlined in the chalky soil. It is not known what action Fred was involved in when he was killed.

Fred Bird had enlisted at the age of sixteen. A comment under the photograph published in “Berkshire and The War” states that he had been in the Scouts for several years and was a “piper” in the YMCA He was also a native of Newtown. Fred had reached the rank of Lance Corporal and had fought in the Dardanelles and France. He was reported missing in November 1916 this was later confirmed as killed in action, he was in his 19th year.

“In Memoriam” The Standard 24th November 1917 gives the following details, the youngest son of the late George Bird of Reading and Mrs. Bird of Mentone, Melbourne, and brother of Mrs. Wilkinson, Recreation Rd. Tilehurst. In addition is a poem

He heard the call of his country,

Far o’er the sea he came,

On Britain’s Roll of Honour

You’ll find the brave boy’s name.

The path of duty is the way to glory.

The 1911 census indicates that Fred and his family lived at 15 School Terrace, Newtown. His sister Ivy, then 15, was two years older than Fred. Fred’s father, George, was aged 72 and his occupation was given as Army Pensioner and Biscuit Factory Labourer. Fred’s mother, Kate was aged 56. Fred and George had been married for sixteen years.