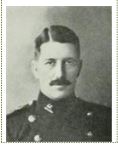

William Arthur Ayres

Private 14328

8th Battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment

and Sapper 243961 Royal Engineers

William Arthur Ayres was the son of William Reynolds Ayres and Minie Ayres of

9, St. Edwards Road, Reading. William was the eldest of their five children. The 1911 census has him recorded as 13 years old and still attending school, this would give his year of birth as 1898. His brothers and sisters were: John 12, Harold 8, Elsie May 10 and Gladys 4. William’s father’s occupation was given as a carpenter and joiner. Living with the family at that time was Phoebe age 85 who is recorded as an aunt.

William’s military papers are also available through Ancestry UK. He attested to the Royal Berkshire Regiment on 7 September 1914. William gives his age as 19years and 1 month and his occupation as a brass finisher. Local newspapers give his age at death as 19 or 20 years. From the evidence available it seems that William lied about his age and enlisted at the age of 16. His attestation papers record him as ‘head’.

William served just under 3 years. As the information below shows William was injured at Loos. Whilst recovering was put on a charge for breaking out of camp and remaining absent for 3 days and 15 hours. What he was doing during his absence is not stated. His punishment was loss of 4 days pay and 14 days confined to barracks. In 1916 he was hospitalised for an appendectomy. When he had recovered he returned to France where he transfered to the Royal Engineers. The Reading Standard ‘In Memoriam 1919’ states ‘Killed in Action.’ where as grave registration states died of sickness. William’s military papers confirm that he did indeed die of sickness. His records provide comprehensive notes of the cause of death which is given as menigitis. This developed because of previous operation for a mastoid. The original problem with his ear was given as being due to the effects of the guns and shelling whilst serving on the Somme.

This text which follows is taken from the authors unpublished manuscript – “The School, the Master, the Boys and the VC.” which is about the men named on the Alfred Sutton School War Memorial. It gives further details about William Arthur Ayres military service.

William Ayres took park in the Battle of Loos in September 1915. Although injured he survived the severe machine gun fire of the battle and found himself on the outskirts of Hulluch village near the Lens-La Bassée road. He was in a signalling section of his unit and part of a small scouting party sent to reconnoitre the village. William’s own account of his experiences in front of Hulluch was published in the book Responding to the Call authored by Colin Fox et al:

“We had captured three lines, most of the enemy not waiting for the bayonet. We signallers had two wires across to the almost captured village (of Hulluch). Corporals Giddings and Shirley took another wire across. We were in sight of the village and they were

trying to stop us: three men with a quick fire gun. The shells did not hit but the sniper did and

put one through my shoulder, mess can, coat and everything. My two mates dropped down, put a field dressing on my wound and ran on. I believe they got the wire across. I lay low

‘till the sniper in the trees had wasted most of his ammunition and then I made

a bolt for it and got to the field dressing station.”

William was lucky to reach the dressing station and obtain treatment and evacuation to safer territory. The survivors of the battalion were less fortunate with many of them suffering from thirst and hunger until they were finally relieved on 28 September.

William Ayres was hospitalised in Warrington but within a matter of months he found himself back at the front. Having recovered from the wounds received at Loos in autumn 1915 William found himself back with his unit during the Battle of the Somme. The 8th Battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment was essentially in support during three separate engagements, 14 July, 18 August and 3 September. The battalion arrived in the battle zone on 9 July and went into action for the first time early on the morning of the 11 July; orders had been given to hold, at all costs, the village of Contalmaison, in the area of Mametz Wood. The area was one of destruction, the village had changed hands several times and not a house was standing. However, the battalion managed to consolidate the line. On the evening of the 12 July patrols were sent out and preparations made for an attack on the 14 July that, in the event, was very successful for the Fourth Army of which the battalion was a part. It was during this period that William Ayres won the Military Medal. The London Gazette 1 September1916 records the citation ‘for good work and bravery.’ The action was ‘mending a telephone line at great risk,’ also commended with him was Private R. Slyfield of Reading. (Details about R.Slyfied, Robert, and his brother also R.Slyfield, Richard, who is buried in the cemetery can be found on this site.)

It is not clear what other actions he was involved in but, having survived the Somme campaign, the coldest winter for many years and the early actions of 1917, which included the Battle of Arras, he transferred to the Royal Engineers. The Royal Engineers had a major responsibility for signalling and, initially at least, he is believed to have continued his work as a signaller. This was a dangerous and vital job. Communications with the front line were often broken and the signaller had the job of effecting repairs under the most trying of circumstances.”

William died in France on 22 July 1917 and is buried at Merville Communal Cemetery Extension, location I. B. 43. The town of Merville is situated around a waterway ‘crossroads.’ The River Lys, runs from west to east, the Canal de la Nieppe runs from the north to west skirting the Forêt de Nieppe; the Canal d’ Aire runs to the southwest. It is not known exactly what William’s work was but he was serving in the Inland Waterways Salvage Unit at the time of his death.

William was also a puzzel in other ways. William’s family were atheists and his headstone does not bear the usual cross and has the following commemoration:

TO LIVE IN THE HEARTS

OF THOSE WE LOVE

IS NOT TO DIE

“HOW HE LOVED”

However, Local newspapers at the time of his death stated that prior to the war William was employed in the Signal Works department of the Great Western Railway whether this has anything to do with being a ‘brass finisher’ as given on the attestation papers is not known.

William was a member of Reading University College and is commemorated on that war memorial. His father, William Reyolds Ayres was an ardent socialist and trades unionist; he was the first Labour member of the Reading Town Council.