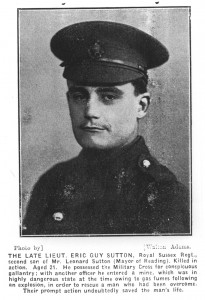

Eric Guy Sutton M.C.

2nd Lieutenant

7th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment

|

Eric Guy Sutton was the grandson of Martin Hope Sutton, one of the founders of the Sutton Seeds business and the second son of Leonard Goodhart Sutton and his wife Mary Charlotte Sutton (nee Seaton). His mother probably died in childbirth in July 1900 giving birth to his only sister Emily May.

He was educated at Rugby where he was a keen rugby footballer. He had always expressed an ambition to enter the Army but after leaving school he decided on a business career. He spent a year in France and six months travelling in America preparing for this and was due to return to Reading in the autumn of 1914. On the outbreak of war he returned from California and was gazetted into his regiment in September 1914. In the spring of 1915 he went to the front and in June he was appointed lieutenant.

Eric Guy Sutton was awarded the Military Cross for “conspicuous gallantry on the night of September 12th 1915, near Armentieres. With another officer he entered a mine, which was in a highly dangerous state at the time owing to gas fumes following an explosion, in order to rescue a man who had been overcome. Their prompt action undoubtable saved the man’s life.” He was decorated a Buckingham Palace on 23 February 1916.

On hearing of the distinction awarded to him he wrote:

“On looking back upon the incident it seems a very paltry affair. It was over in a few moments. One of the things prominent in my mind is – How many thousands more, especially in Gallipoli, deserve the honour much more that I do!”

He was killed in action on 8 April 1916 aged 21 and is buried in Vermelles British Cemetery, Pas de Calais, grave location II. D. 20.

The circumstances of his death were reported as follows:

He was in charge of the Lewis (machine) guns, as he had been for some time,prior to which he had temporary command of his company. At 6.30 p.m. on 8th april 1916 the Germans exploded a mine under part of the Britishd trenches blowing down the parapet and filling parts of the trench, leaving a portion exposed to rifle fire.

It appeard that in order to get his guns into position again he had to cross the exposed portion and examine the crater, and was shot by a sniper in the neck and died instantly.

Employees of the Sutton Seed firm were alerted to the sad news of his death by a flag flying at half mast over the business premises.