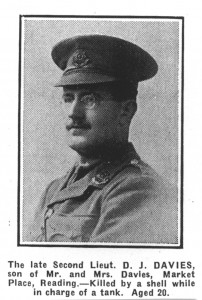

David James Davies

Second Lieutenant

Machine Gun Corps attached to “C” Battalion Tank Corps.

Division 13

|

David James Davies was the son of Mr Walter and Mrs Florence Esther Davies of 32. Market Place, Reading. It was from that address that Walter Davies ran his shop selling china and glass. In 1911 David was 13 and still at school. HIs older sister Ester Madeline is described as working part time in the shop and part time as a student. David’s oldest sister Florence was not living with the family in 1911. He was commemorated on a his family’s grave.

The Third Battle of Ypres began on 31st July 1917. A bombardment had begun fifteen days earlier and over four million shells had been fired. (One million had been fired prior to the Battle of the Somme). At 3.50a.m. the assaulting troops of the Second and Fifth Armies, with a portion of the French First Army lending support on the left, moved forward, accompanied by 136 tanks. The Tank Corps was only four days old. Previously it had been known as the Heavy Branch, Machine Gun Corps, a name adopted for purposes of secrecy at their formation. Preparations for the battle had taken place in dry weather but on the first day the weather broke and three-quarters of an inch (21.7mm) of rain soaked the battlefield. Men and tanks moved forward behind the creeping barrage over ground churned and cratered by years of shelling. The surface was softened by the rain but, for all that only two tanks bogged down at the commencement of battle although many ditched later. A map was prepared by Major Fuller, Staff Intelligence Officer of the Tanks, of the ground over which the tanks were expected to attack. Where he expected the ground to be marshy, he coloured the area blue. What he saw appalled him, it was three-quarters of the battlefield. He sent the maps to Haig’s GHQ so that the Commander in Chief could judge conditions for himself. However, the map was intercepted by Charteris who refused to show it to the Commander in Chief on the grounds that it would depress him. Only 48% of the tanks reached their first objective. Although there was some progress in the early part of the day by late morning the familiar breakdown in communications between infantry and guns occurred. At two in the afternoon the Germans began to counter attack with a heavy shelling and this together with the heavy rain turned the battle field into soupy mud. A halt to the offensive was called until the 4th August. However, Haig insisted that the attack had been “highly satisfactory and the losses slight”. By comparison with the Somme, when 20,000 men had died on the opening day, only about 8,800 men were reported dead or missing. The total wounded, including those of the French Army, numbered 35,000, the Germans suffered a similar number. However, the Germans remained in command of the vital ground and committed none of their counter attack divisions. Prince Rupprecht , in his diary recorded that he was “very satisfied with the results”.

It is not known exactly when and where David James Davies was killed in command of his tank but it was struck by a shell on the opening day of the battle. David Davies had no known grave and his name is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial, Panel 56. He was aged 20.